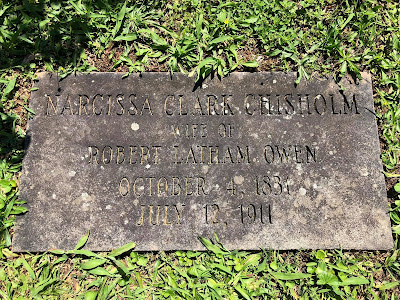

On the Spring Hill Cemetery website under “Notables,” Narcissa C. Owen (183l-1911) is listed as "’The Indian Princess’ who lived at Point of Honor during the Civil War.” She is also listed as an “artist and the daughter of Thomas Chisholm, the last hereditary Chief of the Western Cherokees [as well as the] wife of Robert Latham Owen, Sr.” After visiting her grave, I did some research and learned that she wrote Memoirs of Narcissa Owen, 1831-1907, published in 1907.[1] She also was a prominent voice in woman suffrage and the rights of Cherokee people. [2]

While she was a memoirist, she identified as a portrait artist and her most notable works include a notable a self-portrait, and Thomas Jefferson and His Descendants.[3] Her interest in Jefferson was an association with her father, Thomas Chisholm, who received the silver Peace and Friendship medal in recognition of being the last hereditary war chief of the Cherokees from Jefferson in 1808.[4]

Graves of husband and her son.

Born on October 3, 1831 to Thomas Chisholm and Malinda Wharton, Narcissa was the youngest of four children. She was the direct descent of Queen Quatisis, “the lineal successor of the seven original chiefs of Cherokee blood.”[5]

Young Narcissa did not have the easiest upbringing. Her father died in 1834 and her mother was unable to care for all four children so her siblings were sent away to school. She remained with her mother for two years before she was also sent away.[6] When she was nearly 11 years old, she moved in with her older sister. She would go on to a women’s college in Indiana and then attend Miss Sawyer’s Female Seminary in Fayetteville, Arkansas.[7]

|

| The Caney News, (Caney, Kansas: July 21, 1911). |

She married her husband Robert Latham Owen, a descendant of George Washington on October 4, 1853, a day after her nineteenth birthday.[8] And since it sometimes feels like all roads lead to Richmond, Charles Dimmock, the architect who designed Hollywood Cemetery’s 90-foot pyramid that was erected in December 1868, was one of the groomsmen at their wedding.[9] This is a complete aside but while researching Narcissa Owen and then falling down a rabbit hole about Charles Dimmock, I learned that the Hollywood Memorial Association sent him to monitor the exhumation of the Southern remains in the Gettysburg battlefield. It was his report about the horrid conditions and desecration of the graves by farmers that recommended that the bodies be moved to Hollywood.[10]

By the Civil War, Narcissa Owen and her family were living in Lynchburg. Along with five hundred other Lynchburg ladies, she helped provide young recruits with uniforms and hospital supplies. When there weren’t jobs enough jobs for sewing and earning an income, Narcissa Owen collected money from wealthier families to provide for the wives and children of Lynchburg’s soldiers.[11]

In June 1873, her husband passed away. Her son, Robert Latham Owen, Jr. and she moved to the Cherokee Nation. She was offered a position to teach in the Cherokee Female Seminary in 1880 and continued in the position until 1884.

Memoirs of Narcissa Owen, 1907

Although she was always interested in art, she began to focus on learning perspective and oil colors after she left her teaching position.

In 1907, she published her memoirs and then passed away a few years later on July 11, 1911. She was 80 years old.[12]

|

| Epitaph of her son |

[1] Narcissa Owen, Memoirs of Narcissa Owen, 1831-1907, 1907, The place of publication is not identified. Amherst College Digital Collections, Archives & Special Collections, https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:788769/asc:788826

[2] “Mrs. Owen Was Indian Princess,” The Poteau News, (Poteau, Oklahoma: July 20, 1911)2.

[3] Stacie Boston, “Owen's Life Consisted of Love for Art, Music and Her People.” Cherokee Phoenix, March 4, 2021. https://www.cherokeephoenix.org/culture/owen-s-life-consisted-of-love-for-art-music-and-her-people/article_caaf7e08-7cf9-11eb-8e2e-fff0b25be0df.html.

[4] Janet Shaffer. "Narcissa and Robert Owen: The Point of Honor Years." The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 89, no. 2 (1981): 166.

[5] The Caney News, (Caney, Kansas: July 21, 1911).

[6] Shaffer, 155.

[7] Shaffer, 156.

[8] Shaffer, 157.

[9] Shaffer, 156.

[10] Adrienne E. Robertson,"Charles Henry Dimmock (1831–1873)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia, published 2015.

[11] Shaffer, 159.

[12] Shaffer, 167.